Measuring the deformation of building elements engulfed by flames is essential in fire research to improve safety in the event of a fire.

Ideally, the measurement system should be non-contact, able to range at the millimeter to meter scale with sub-mm precision, and have sufficient speed to capture temperature-induced deformations of the target object.

Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have used a laser detection and ranging (LADAR) system to image three-dimensional (3D) objects melting in flames.

The method could offer a precise, safe and compact way to measure structures as they collapse in fires.

Optical range measurements, already used in manufacturing and other fields, may help overcome practical challenges posed by structural fires, which are too hot to measure with conventional electromechanical sensors mounted on buildings.

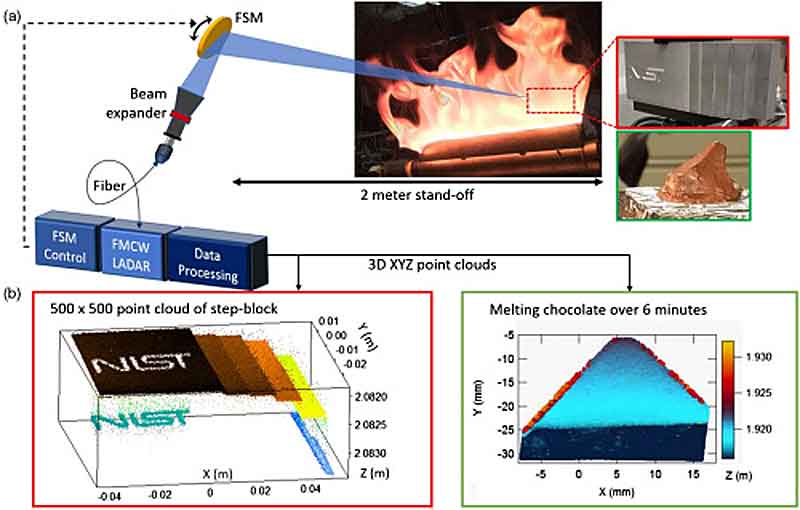

As described in Optica, the NIST demonstration used a commercial LADAR system to map distances to objects melting behind flames that produced varying amounts of soot.

The experiment measured 3D surfaces with a precision of 30 micrometers (millionths of a meter) or better from 2 meters away.

This level of precision meets requirements for most structural fire research applications, according to the paper.

The NIST demonstration focused on pieces of chocolate and a plastic toy.

“We needed something that doesn’t melt too fast or too slow but you still see an effect,” project leader Esther Baumann explained.

“And I like chocolate.”

LADAR offers several advantages as a tool for imaging through flames.

The technique is very sensitive and can image objects even when small amounts of soot are present in the flames.

The method also works at a distance, from far enough away that the equipment is safe from the intense heat of a fire.

Additionally, the instrument can be compact and portable, relying on fiber optics and simple photodetectors.

“The project came together somewhat serendipitously when we got ‘fire people’ talking with ‘optics people,’” NIST structural engineer Matthew Hoehler said.

“The collaboration has not only been fruitful, it’s been fun.”

In the 3D mapping system, a laser sweeps continuously across a band of optical frequencies.

The initial laser output is combined with the reflected light from the target.

The resulting “beat” signals are detected, and this voltage is then analyzed by digital signal processing to generate time-delay data, equivalent to distance. (The difference in frequency between the initial signal and the one received from the target increases with distance.)

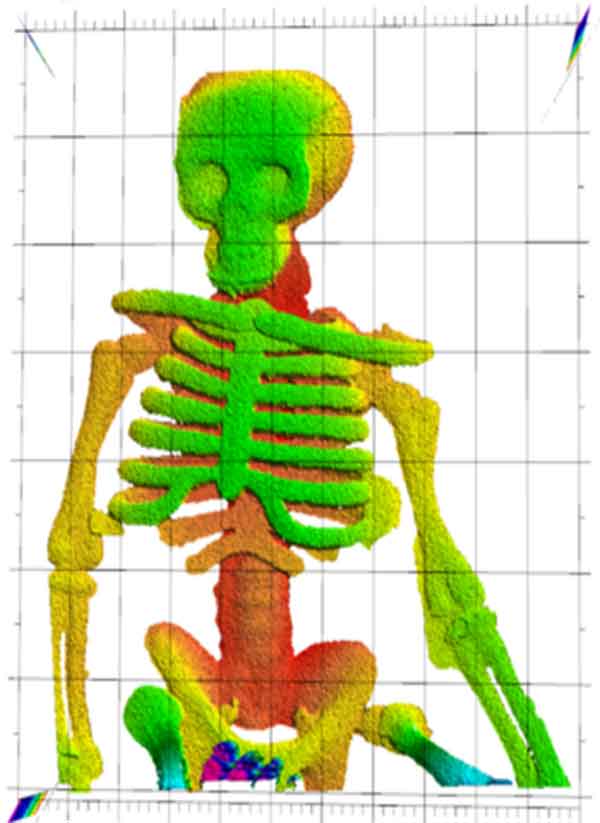

The researchers successfully applied LADAR to measure and map 3D “point clouds”—points are the “voxels” constituting an image—even in a turbulent fire environment with strong signal scattering and distortion.

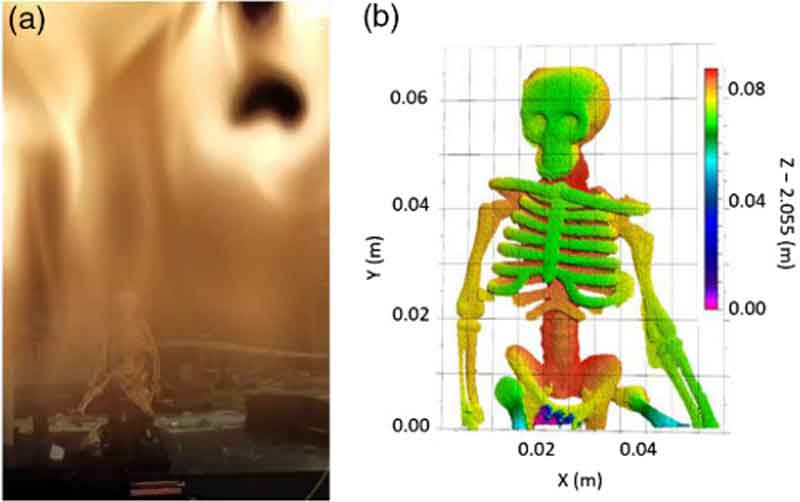

For comparison, the team also made videos of the chocolate as it melted and images of a more complex plastic skeleton. (See below.)

NIST researchers demonstrated that laser ranging could make a continuous series of “point clouds” of a piece of chocolate melting behind flames. The deformation process occurred over 6 minutes but is sped up in the video clip. The false color indicates depth, with blue being the closest and red the farthest away.

For the melting chocolate, each LADAR frame consisted of 7,500 points sufficient to capture the chocolate deformation process.

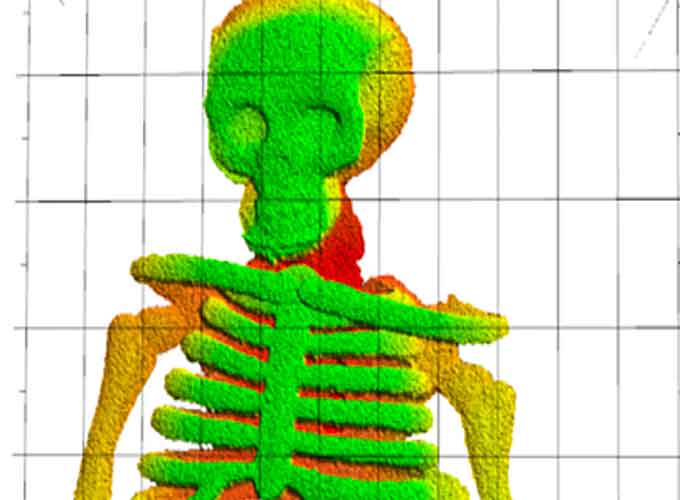

The plastic skeleton was barely visible in the conventional video, but the 3D point cloud revealed complex shapes otherwise hidden behind flames—details of the ribcage and hips.

The researchers determined that the LADAR system was fast enough to overcome signal distortions, and that deflections of the laser beam due to the flames could be accommodated by averaging the signals over time, to retain high precision.

The initial experiments were conducted with flames just 50 millimeters wide on lab burners at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The preliminary results suggest that the LADAR technique could be applied to larger objects and fires.

The NIST team now plans to scale up the experiment, first to make 3D images of objects through flames about 1 meter wide, and if that works, to make quantitative observations of larger structural fires.

The NIST team now plans to scale up the experiment, first to make 3D images of objects through flames about 1 meter wide, and if that works, to make quantitative observations of larger structural fires.

Paper: E.W. Mitchell, M.S. Hoehler, F.R. Giorgetta, T. Hayden, G.B. Rieker, N.R. Newbury and E. Baumann. 2018. Coherent laser ranging for precision imaging through flames. Optica. Published August 8, 2018. DOI: 10.1364/OPTICA.5.000988