Guest Editorial by Ben Aubin, Security Specialist

I. Summary

With an increase in active shooter incidents comes the inevitable evolution in the shootings themselves.

Unfortunately, while active shooter incidents remain fluid and dynamic the solutions and/or preventative measures appear to be stagnate.

There are currently two models in wide spread use for dealing with active shooter scenarios.

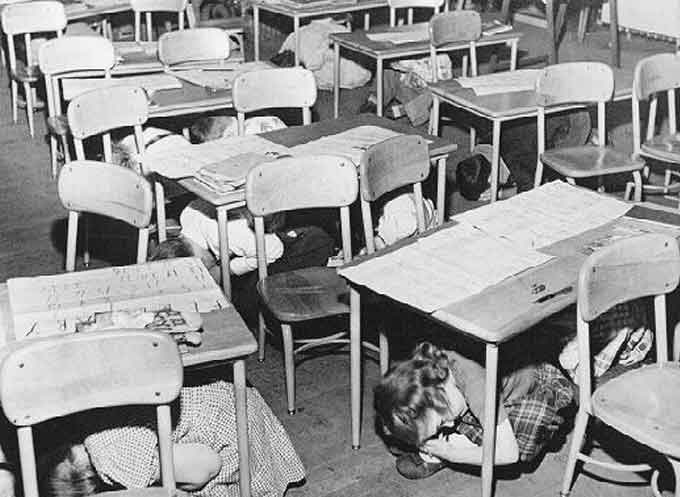

The first, shelter-in-place, a remnant of the Cold War era intended to address chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) attacks by having occupants seek shelter within the confines of the structure currently occupied.

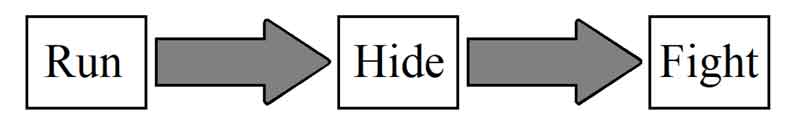

The second, run-hide-fight, a modernized approach to shelter-in-place which stresses the need to:

- Move away from immediate danger exiting the structure if possible

- To seek cover or concealment if this is not possible, and

- If all else fails to employ maximum resistance to the threat in the hopes of incapacitating the shooter

In this piece we will look at both models, how they are taught and some preventative measures that can be employed within the context of large assembly environments such as public education centers.

II. Problems

Numerous problems exist within our current educational system that can be detrimental to dealing with the problem of active shooters.

First, a templated approach by non-security personnel in the development of preventative measures and responses to active shooter events.

With the aim of dispersing relevant information to the masses, a prepackaged approach is often adopted that fails to highlight many aspects unique to each location.

With the aim of dispersing relevant information to the masses, a prepackaged approach is often adopted that fails to highlight many aspects unique to each location.

While this certainly provides for the dissemination of information quickly it takes a “one-size-fits-all” approach which over simplifies the problem in the hopes of providing the appearance of security without actually having it.

Second, a consistency in the methodological system being taught.

Many times the run-hide-fight methodology is taught within the educational system without the application of “fight”.

However, a lack of focus on the fight side of the equation renders the run-hide-fight methodology to simply that of run-hide, which parallels exactly the shelter-in-place model which was in no way developed for use to combat active shooters.

Finally, even in places where run-hide-fight has been instructed it is often instructed in a linear manner.

The train of thought is that:

- IF one can run, he should.

- IF one cannot, they should hide.

- IF one cannot hide, they should fight.

However, this linear progression fails to address the fluidity of the scenario and foster a proper mindset that sees the run-hide-fight methodology not as a linear progression but a continuum of sort, or a cyclical progression.

III. Solutions

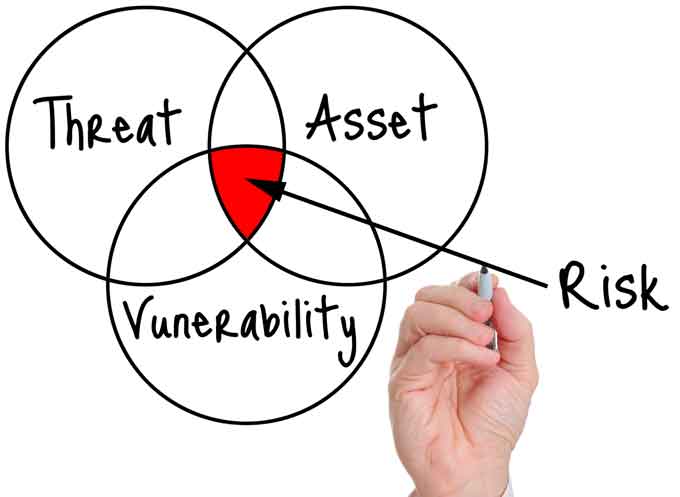

The one size fits all approach to both preventative and response development removes the possibility of highlighting the strengths and weaknesses within a particular environment.

This is one of the best reasons for local school boards to employ security professionals within the industry in the development of preventative measures and responses.

An understanding of architectural, structural and fire suppression systems in addition to that of security can be an enormous asset in the development of a vulnerability assessment and the development of responses tailored to uniqueness of a particular location.

An example of this might be an assessment that highlights the International Building Code (IBC) and National Fire Prevention Association (NFPA) requirements for classroom doors to be outward swinging, solid core doors.

The addition of type 1 construction and concrete non-flammable materials results in nearly every classroom being of sufficient ballistic protection to repel a shooter from within the corridors, reducing travel distance greatly and thereby minimizing occupant exposure to potential threats.

Additionally, taking this thinking forward one could employ readily available technology in the form of card key access as a form of entrance denial to would-be shooters seeking to gain access to classrooms.

This technology is already in wide spread use throughout the hospitality industry for guests to access areas of hotels.

Cards can be worn as ID badges by teachers allowing teachers to access and deny access to their classrooms at will.

The locking mechanism locks automatically upon closure and can only be opened through the use of a card key, master card key or from the inside of the room as per egress requirements.

The second problem mentioned was that of consistency of methodologies taught within the school system as a whole.

As mentioned earlier, omitting the “fight” portion from run-hide-fight renders the aforementioned methodology useless.

This is not only because run-hide is nothing more than repackaged shelter-in-place but also because it fails to address to the psychological aspect inherent in run-hide-fight, namely a desire to live.

Without the psychological aspect one has resigned their safety to that of the cunning and moral fortitude of their attackers, both of which are largely on display in the worst sense by virtue of the fact that the shooter is even present and engaged in the act to begin with.

While one may cringe at the thought of telling a middle or high school age child that he/she might be required to put up maximum resistance to a would-be attacker, the thought of teaching children to simply curl up into the fetal position is equally reprehensible.

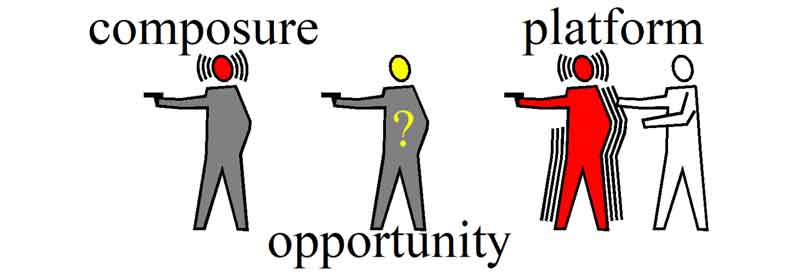

An examination of “what the shooter needs” to accomplish his/her task can be reverse engineered to develop simple responses that systematically remove the 3 components that must be present for any shooter to employ accurate fire on a target.

These components can be remembered using the acrostic: C.O.P.

IV. COP

C.O.P. stands for “composure, opportunity, and platform.

For any shooter to employ accurate fire he/she must have all three components.

They must possess composure in the sense of stress mitigation.

While running is always preferable to entering a gun fight unarmed we must understand that abandoning the fight entirely allows the shooter to retain his composure by not inducing stress on them.

This is a basic concept that is often exemplified in force on force training within the law enforcement and military training communities.

Shooting is one thing, shooting against a foe who is intent on not letting you do so is an entirely different animal.

Even among trained individuals, accuracy of fire is reduced by as much as 50% when external stressors are added in.

The “opportunity” within the COP acrostic refers to giving the shooter an opportunity to place rounds on target.

If a shooter does not have the opportunity to shoot you, you can’t be shot.

Now this cannot be removed entirely but it can be decreased through the use of movement, cover and concealment.

All 3 of these are necessary to the component “opportunity”.

A moving target is more difficult to hit than a stationary target.

Additionally, a target that resides behind the safety of ballistically resistant cover also cannot be shot.

Finally, removing the ability for the shooter to see a target through the use of concealment also greatly decreases the shooter’s ability to accurately put rounds on target.

The final component is that of “platform” or the more familiar term stance.

All weapon systems require the use of a stable shooting platform in order to accurately operate.

Whether competitive target shooting or tactical shooting both disciplines training regimes highlight the effect that an unstable platform can have on accuracy.

We mentioned above that introducing psychological external stressors can reduce accuracy by as much as 50%. But imagine now the inclusion of physical stressors as well.

Grabbing the gun, wrestling with the attacker, throwing objects that force the attackers physiological body alarm response mechanism to engage.

Even among highly trained individuals the ability to master one of these components takes years and mastering all 3 can take a lifetime.

We have to stop looking for responses in the area of “certainty” within these types of dynamic engagements and resolve ourselves to the fact that these are matters of percentages.

Certain actions will increase the shooters effectiveness, others will decrease them.

But, all of these components reside within our control unless we surrender them.

Our goal then is to minimize our exposure to the greatest extent possible by harnessing our most basic instinct and greatest asset, the will to live.

The benefits of a positive “will to live” mindset do not end with the fight but rather go on to foster creativity and lead into the third and final issue mentioned, linear versus cyclical progression in the teaching structure of the run-hide-fight methodology.

As mentioned above, all current models of either methodology taught (which omits the fight portion) result in students and faculty seeking shelter within a classroom while the shooter seeks to make entry.

This defensive posture, a result of this reticent mindset places the students and faculty in a reactive mode against an aggressive, armed opponent with intent.

A fight mentality properly fostered and filtered through the lens of run-hide-fight as a continuum reformats the train of thought from:

- IF one cannot run, they should hide.

- IF they cannot hide they should fight.

To:

- RUN.

- IF you cannot run, HIDE.

- But as soon as you can, run again and start the progression over.

IF you cannot run or hide, FIGHT. But as soon as you can, run again and start the progression over.

In the case of many schools which are designed and constructed in the manner mentioned earlier, students have benefit of moderate ballistic protection as provided by the fire-resistant shell of the classroom to serve as a barrier.

However, where the current model would have the students take refuge inside the classroom, the cyclical understanding would have the students then reevaluate if in fact they can take up the “run” portion again.

With current building codes and NFPA requirements most assembly areas and classrooms are required (dependent on occupant load) to have two forms of egress.

First floor classrooms can utilize fire exit windows or alternate adjoining classrooms doors to put distance between themselves and the shooter with the ultimate goal of exiting the building entirely, the opposite of which is taught today.

This employs a tried and tested military principle known as “getting off the X” to put as much distance and obstacles between the threat and ourselves and then reevaluate.

V. Conclusion

These are but a few of the issues and examples that can be addressed with an independent evaluation of each site.

The same model can be employed in other gathering venues such as professional buildings, government centers and places of worship.

Each site should be individually assessed by competent security professionals with the requisite background and skills in associated disciplines to determine a site-specific model, develop response plans and provide training accordingly.

Active shootings are not going away.

Whether a result of political polarization fueled by societal division or an increase in terrorism and the notoriety that goes along with accomplishing an agenda by any means.

Active shootings will continue to evolve with each response and a methodology that allows for individual and fluid development is needed to get ahead of the rising threat.

Ben Aubin, Security Specialist, Tactical Intelligence International, President, Redbeard Combatives, Inc., Vice President, Automated Consulting Services, Inc.

About the Author:

Ben has over 13 years of experience working with the DoD and Private Security sectors, with a focus on training, physical security, and vulnerability assessments.

He has deployed multiple times to austere locations including the Middle East and South America, as well as numerous at sea deployments providing vessel security aboard commercial ships transiting high-risk waters. Ben was the Assistant Team Leader on a US Department of State contract supporting humanitarian operations in Bolivia and Peru, conducting site security surveys and PSD operations in areas of civil unrest.

He further provided physical security and personnel escort duties, working alongside U.S. military personnel at a forward operating base in Northern Afghanistan.

Ben has provided courses of instruction in combatives to Army’s 101st Airborne Division and members of the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office and is one of TII’s primary self-defense and hand-to-hand combat instructors.

Ben has provided courses of instruction in combatives to Army’s 101st Airborne Division and members of the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office and is one of TII’s primary self-defense and hand-to-hand combat instructors.

Additionally, Ben holds rating of general contractor in the state of Florida with experience in design and construction supervision of over 150 hotels, and countless other commercial developments.

He is an experienced civil and structural designer with over 20 years’ experience in the field and holds advanced degrees in Intelligence Studies from American Military University, with advanced certifications in Counter Intelligence.

He is a certified protection specialist, weapons instructor, and Florida Licensed Private Investigator.