By Robert Wiblin, 80,000 HOURS

“There is no doubting the force of [the] arguments … the problem is a research challenge worthy of the next generation’s best mathematical talent. Human civilisation is at stake.”

– Clive Cookson, Science Editor at the Financial Times

Around 1800, civilization underwent one of the most profound shifts in human history: the industrial revolution.

This wasn’t the first such event – the agricultural revolution had upended human lives 12,000 years earlier.

A growing number of experts believe that a third revolution will occur during the 21st century, through the invention of machines with intelligence which far surpasses our own.

These range from Stephen Hawking to Stuart Russell, the author of the best-selling AI textbook, AI: A Modern Approach.1

Rapid progress in machine learning has raised the prospect that algorithms will one day be able to do most or all of the mental tasks currently performed by humans. This could ultimately lead to machines that are much better at these tasks than humans.

These advances could lead to extremely positive developments, presenting solutions to now-intractable global problems, but they also pose severe risks.

Humanity’s superior intelligence is pretty much the sole reason that it is the dominant species on the planet. If machines surpass humans in intelligence, then just as the fate of gorillas currently depends on the actions of humans, the fate of humanity may come to depend more on the actions of machines than our own.

For a technical explanation of the risks from the perspective of computer scientists, see these papers.8 11

This might be the most important transition of the next century – either ushering in an unprecedented era of wealth and progress, or heralding disaster.

But it’s also an area that’s highly neglected: while billions are spent making AI more powerful,12 we estimate fewer than 100 people in the world are working on how to make AI safe.4

This problem is an unusual one, and it took us a long time to really understand it. Does it sound weird? Definitely. When we first encountered these ideas in 2009 we were sceptical. But like many others, the more we read the more concerned we became.7

We’ve also come to believe the technical challenge can probably be overcome if humanity puts in the effort.

Working on a newly recognized problem means that you risk throwing yourself at an issue that never materializes or is solved easily – but it also means that you may have a bigger impact by pioneering an area others have yet to properly appreciate, just like many of the highest impact people in history have done.

In what follows, we will cover the arguments for working on this area, and look at the best ways you can contribute.

This is one of many profiles we’ve written to help people find the most pressing problems they can dedicate their careers to solving. Learn more about how we compare different problems, how we try to score them numerically, and how this problem compares to the others we’ve considered so far.

Summary

Many experts believe that there is a significant chance that humanity will develop machines more intelligent than ourselves during the 21st century. This could lead to large, rapid improvements in human welfare, but there are good reasons to think that it could also lead to disastrous outcomes.

The problem of how one might design a highly intelligent machine to pursue realistic human goals safely is very poorly understood.

If AI research continues to advance without enough work going into the research problem of controlling such machines, catastrophic accidents are much more likely to occur. Despite growing recognition of this challenge, fewer than 100 people worldwide are directly working on the problem.

| Recommendation | Recommended – first tier | This is among the most pressing problems to work on. |

| Level of depth | Medium-depth | We’ve interviewed at least five people with relevant expertise about this problem and done an in-depth investigation into a least one of our key uncertainties concerning this problem, then fully written up our findings. It’s likely there remain some gaps in our understanding. |

| Factor | Score (using our rubric) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Scale | 15 / 16 | We estimate that the risk of a serious catastrophe caused by machine intelligence within the next 100 years is between 1 and 10%. |

| Neglectedness | 8 / 12 | $10m of annual funding. |

| Solvability | 4 / 8 | We think a doubling of effort would reduce the size of the existing risk by around 1%. |

Summary of the best ways to work on this problem

- Conduct technical research into how to keep an intelligent machine’s actions and goals aligned with human intentions.

- Conduct strategic research into how governments should work to incorporate intelligent machines into society safely.

- Indirectly contribute to a solution, for example by publicizing the cause and increasing the number of people concerned about the risks posed by artificial intelligence.

What is this profile based on?

We spoke to: Prof Nick Bostrom at the University of Oxford, the author of Superintelligence; a leading professor of computer science; Jaan Tallinn, one of the largest donors in the space and the co-founder of Skype; Jan Leike, a machine learning researcher now at DeepMind; Miles Brundage, an AI policy researcher at the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University; Nate Soares, the Executive Director of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute; Daniel Dewey, who works full-time finding researchers and funding opportunities in the field; and several other researchers in the area. We also read advice from David Krueger, a Machine Learning PhD student.

Why work on this problem?

The arguments for working on this problem area are complex, and what follows is only a brief summary. If you prefer video, then see this TED talk:

Those who are already familiar with computer science may prefer to watch this talk by University of California Berkeley Professor of Computer Science Stuart Russell instead, as it goes further into potential research agendas.

If you want to go further still, and have some time, then we’d recommend reading Superintelligence: Paths, Strategies, Dangers, by Oxford Professor Nick Bostrom. The Artificial Intelligence Revolution, a post by Tim Urban at Wait But Why, is shorter and also good (and also see this response).

Recent progress in machine learning suggests that AI’s impact may be large and sudden

When Tim Urban started investigating his article on this topic, he expected to finish it in a few days. Instead he spent weeks reading everything he could, because, he says, “it hit me pretty quickly that what’s happening in the world of AI is not just an important topic, but by far the most important topic for our future.”

In October 2015 an AI system named AlphaGo shocked the world by defeating a professional at the ancient Chinese board game of Go for the first time. A mere five months later, a second shock followed: AlphaGo had bested one of the world’s top Go professionals, winning 4 matches out of 5.

Seven months later, the same program had further improved, crushing the world’s top players in a 60-win streak. In the span of a year, AI had advanced from being too weak to win a single match against the worst human professionals, to being impossible for even the best players in the world to defeat.

This was shocking because Go is considered far harder for a machine to play than Chess. The number of possible moves in Go is vast, so it’s not possible to work out the best move through “brute force”. Rather, the game requires strategic intuition. Some experts thought it would take at least a decade for Go to be conquered.15

Since then, AlphaGo has discovered that certain ways of playing Go that humans had dismissed as foolish for thousands of years were actually superior. Ke Jie, the top ranked go player in the world, has been astonished: “after humanity spent thousands of years improving our tactics,” he said, “computers tell us that humans are completely wrong. I would go as far as to say not a single human has touched the edge of the truth of Go.”2

The advances above became possible due to progress in an AI technique called “deep learning”. In the past, we had to give computers detailed instructions for every task.

Today, we have programs that teach themselves how to achieve a goal – for example, a program was able to learn how to play Atari games based only on reward feedback from the score. This has been made possible by improved algorithms, faster processors, bigger data sets, and huge investments by companies like Google.

It has led to amazing advances far faster than expected.

But those are just games. Is general machine intelligence still far away? Maybe, but maybe not. It is really hard to predict the future of technology, and lots of past attempts have been completely off the mark. However, the best available surveys of experts assign a significant probability to the development of powerful AI within our lifetimes.

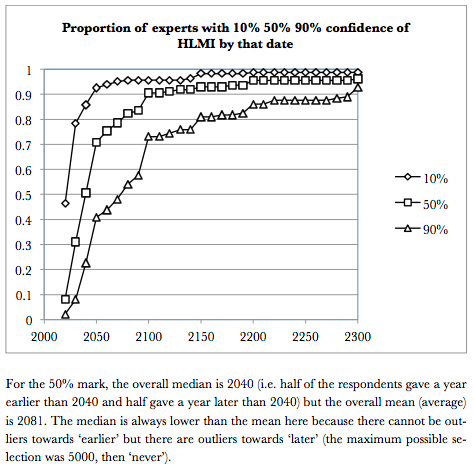

One survey of the 100 most-cited living computer science researchers, of whom 29 responded, found that more than half thought there was a greater than 50% chance of “high-level machine intelligence” – one that can carry out most human professions at least as well as a typical human – being created by 2050, and a greater than 10% chance of it happening by 2024 (see figure below).1 9

When superintelligent AI arrives, it could have huge positive and negative impacts

If the experts are right, an AI system that reaches and then exceeds human capabilities could have very large impacts, both positive and negative.

If AI matures in fields such as mathematical or scientific research, these systems could make rapid progress in curing diseases or engineering robots to serve human needs.

On the other hand, many people worry about the disruptive social effects of this kind of machine intelligence, and in particular its capacity to take over jobs previously done by less skilled workers. If the economy is unable to create new jobs for these people quickly enough, there will be widespread unemployment and falling wages.13 These outcomes could be avoided through government policy, but doing so would likely require significant planning.

However, those aren’t the only impacts highly intelligent machines could have.

Professor Stuart Russell, who wrote the leading textbook on artificial intelligence, has written:3

‘Success brings huge risks. … the combination of [goal] misalignment with increasingly capable decision-making systems can lead to problems – perhaps even species-ending problems if the machines are more capable than humans.’

Here is a highly simplified example of the concern:

The owners of a pharmaceutical company use machine learning algorithms to rapidly generate and evaluate new organic compounds.

As the algorithms improve in capability, it becomes increasingly impractical to keep humans involved in the algorithms’ work – and the humans’ ideas are usually worse anyway.

As a result, the system is granted more and more autonomy in designing and running experiments on new compounds.

Eventually the algorithms are assigned the goal of “reducing the incidence of cancer,” and offer up a compound that initial tests show is highly effective at preventing cancer. Several years pass, and the drug comes into universal usage as a cancer preventative…

…until one day, years down the line, a molecular clock embedded in the compound causes it to produce a potent toxin that suddenly kills anyone with trace amounts of the substance in their bodies.

It turns out the algorithm had found that the compound that was most effective at driving cancer rates to 0 was one that killed humans before they could grow old enough to develop cancer.

The system also predicted that its drug would only achieve this goal if it were widely used, so it combined the toxin with a helpful drug that would incentivize the drug’s widespread adoption.

Of course, the concern isn’t about this example specifically, but rather similar unintended consequences. These reemerge for almost any goal researchers have yet come up with to offer a superintelligent machine.10

And all it takes is for a single super-intelligent machine in the world to receive a poor instruction, and it could pose a large risk.

The smarter a system, the harder it becomes for humans to exercise meaningful oversight. And, as in the scenario above, an intelligent machine will often want to keep humans in the dark, if obscuring its actions reduces the risk that humans will interfere with it achieving its assigned goal.

You might think ‘why can’t we just turn it off?’, but of course an intelligent system will give every indication of doing exactly what we want, until it is certain we won’t be able to turn it off.

An intelligent machine may ‘know’ that what it is doing is not what humans intended it to do, but that is simply not relevant. Just as a heat-seeking missile follows hot objects, by design a machine intelligence will do exactly, and literally, what we initially program it to do.

Unfortunately, intelligence doesn’t necessarily mean it shares our goals. As a result it can easily become monomaniacal in pursuit of a supremely stupid goal.

The solution is to figure out how to ensure that the instructions we give to a machine intelligence really capture what we want it to do, without any such unintended outcomes. This is called a solution to the ‘control’ or ‘value alignment’ problem.

It’s hard to imagine a more important research question.

Solving the control problem could mean the difference between enormous wealth, happiness and health — and the destruction of the very conditions which allow humanity to thrive.

Few people are working on the problem

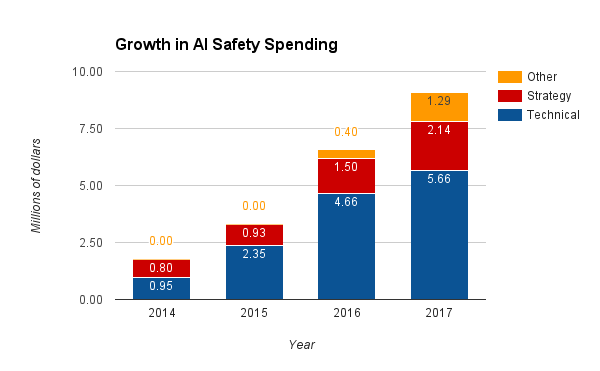

While the stakes seem huge, the effort being put into avoiding these hazards is small. Global spending on research and action to ensure that machine intelligence is developed safely will come to only $9 million in 2017.4

By comparison, over 100 times as much is spent trying to speed up the development of machine intelligence,12 and 26,000 times as much is spent on biomedical research.5

That said, the field of AI safety research is growing quickly – in 2015, total spending was just $3 million.

Technical research refers to work in mathematics and AI to solve the control problem. Strategy research is focused on broader questions about how to safely develop AI, such as how it should be regulated.

Since so few resources have gone into this work so far, we can expect to make quite rapid progress early on: the easiest and most useful discoveries are still available for you to make.

And the problem has become more urgent in the last few years due to increased investment and progress in developing machine intelligence.

There are clear ways to make progress

As we’d expect from the above, recent investment into technical research on the control problem has already yielded significant results. We’ve detailed some of these findings in this footnote.14

While few of the technical issues have been resolved, we have a much clearer picture today of how intelligent systems can go wrong than a few years ago, which is the first step towards a solution.8

There has also been recent progress on better understanding the broader ‘strategic’ issues around AI. For instance, there has been research into how the government should respond to AI, covering arms races,16 the implications of sharing research openly,17 and the criteria on which AI policy should be judged.18 That said, there is still very little written on these topics, so single papers can be a huge contribution to the literature.

Even if – as some have argued – meaningful research were not possible right now, it would still be possible to build a community dedicated to mitigating these risks at a future time when progress is easier.

Work by non-technical people has helped to expand funding and interest in the field a great deal, contributing to the recent rapid growth in efforts to tackle the problem.

Example: Paul Christiano used his math skills to tackle technical challenges

Paul Christiano was an outstanding mathematics student who moved to Berkeley to learn more about machine intelligence safety research several years ago.

Since then, he has done research in learning theory and independently wrote about AI safety research. This led OpenAI, which has $1 billion in pledged donations to fund the development of safe AI, to offer him a job.

Since then he has helped clarify the precise technical challenges involved in making AI safe, making it easier for others to contribute to solving them.

What are the major arguments against this problem being pressing?

Not everyone agrees that there is a problem

Here are some examples of counterarguments:

- Some argue that machine intelligences beyond human capabilities are a long way away. For examples of this debate see No, the Experts Don’t Think Superintelligent AI is a Threat to Humanity in the MIT Technology Review, and the responses Yes, We Are Worried About the Existential Risk of Artificial Intelligence, and the AI FAQ.

- Some believe that artificial intelligence, even if much more intelligent than humans in some ways, will never have the opportunity to cause destruction on a global scale. For an example of this, see economist Robin Hanson, who believes that machines will eventually become better than humans at all tasks and supercede us, but that the process will be gradual and distributed enough to ensure that no one actor is ever in a position to become particularly influential. His views are detailed in his book The Age of Em.6

- Some believe that it will be straightforward to get an intelligent system to act in our interests. For an example of this, see Holden Karnofsky arguing in 2012 that we could design AIs to work as passive tools rather than active agents (though he has since changed his view significantly and now represents one of the field’s major funders).

- Neil Lawrence, an academic in machine learning, takes issue with many predictions in Bostrom’s book Superintelligence, including our ability to make meaningful predictions far into the future.

The fact that there isn’t a consensus that smarter than human AI is coming soon and will be dangerous is a relief. However, given that a significant and growing fraction of relevant experts are worried, it’s a matter of prudent risk management to put effort into the problem in case they are right.

You don’t need to be 100% sure your house is going to burn down to buy fire insurance.

We aren’t the most qualified to judge, but we have looked into the substantive issues and mostly found ourselves agreeing with those who are more worried than less.

It may be too early to work on it

If the development of human-level machine intelligence is hundreds of years away, then it may be premature to research how to align it with human values.

For example, the methods used to build machine intelligence may end up being completely different from those we use to develop AI now, rendering today’s research obsolete.

However, the surveys of computer scientists show that there’s a significant chance – perhaps around 10% – that human level AI will arrive in 10-20 years. It’s worth starting now just in case this fast scenario proves to be accurate.

Furthermore, even if we knew that human level AI was at least 50 years away, we don’t know how hard it will be to solve the ‘control problem’. The solution may require a series of insights that naturally come one after another.

The more of those insights we build up ahead of time, the more likely it is that we’ll be able to complete the solution in a rush once the nature of AI becomes clear.

Additionally, acting today could set up the infrastructure necessary to take action later, even if research today is not directly helpful.

It could be very hard to solve

As with many research projects in their early stages, we don’t know how hard this problem is to solve. Someone could believe there are major risks from machine intelligence, but be pessimistic about what additional research will accomplish, and so decide not to focus on it.

It may not fit your skills

Many individuals are concerned about this problem, but think that their skills are not a natural fit for working on it, so spend their time working on something else.

This is likely true for math-heavy technical research roles, though below we also describe operational and support roles that are a good fit for a wider range of people.

Summing up

- It is probably possible to design a machine that is as good at accomplishing its goals as humans, including ‘social’ tasks that machines are currently hopeless at. Experts in artificial intelligence assign a greater than 50% chance of this happening in the 21st century.

- Without careful design for reliability and robustness, machine intelligence may do things very differently than what humans intended – including pursuing policies that have a catastrophic impact on the world.

- Even if advanced machine intelligence does not get ‘out of control’, it is likely to be very socially disruptive and could be used as a destabilizing weapon of war.

- It is unknown how fast progress on this problem can be made – it may be fast, or slow.

What can you do to help?

We’ve broken this section into five parts to cover the main paths to making a difference in this area.

1. Technical research

Ultimately the problem will require a technical solution – humans will need to find a way to ensure that machines always understand and comply with what we really want them to do. But few people are able to do this research, and there’s currently a surplus of funding and a shortage of researchers.

So, if you might be a good fit for this kind of research, it could well be one of the highest-impact things you can do with your life.

Researchers in this field mostly work in academia and technology companies such as Google Deepmind or OpenAI.

You might be a good fit if you would be capable of completing a PhD at a top 20 program in computer science or a similar quantitative course (though it’s not necessary to have such a background). We discuss this path in detail here:

CAREER REVIEW OF TECHNICAL RESEARCH

2. Strategy and policy research

If improvements in artificial intelligence come to represent the most important changes in the 21st century, governments are sure to take a keen interest.

For this reason, there is a lot of interest in strategic and policy research – attempts to forecast how a transition to smarter-than-human machine intelligence could occur, and what the response by governments and other major institutions should be.

This is a huge field, but some key issues include:

- How should we respond to technological unemployment if intelligent systems rapidly displace human workers?

- How do we avoid an ‘arms race’ in which countries or organizations race to develop strong machine intelligences, for strategic advantage, as occurred with nuclear weapons?

- How do we avoid the use of machine intelligence or robots in warfare, where they could have a destabilizing effect?

- If an intelligent system is going to have a revolutionary effect on society, how should its goals be chosen?

- When, if ever, should we expect AI to achieve particular capabilities or reach human-level intelligence?

If we handle these issues badly, it could lead to disaster, even if we solve the technical challenges associated with controlling a machine intelligence. So there’s a real need for more people to work on them.

That said, this is an especially difficult area, because it’s easy to do more harm than good.

For example, you could make an arms race more likely by promoting the idea that machine intelligence can give you a strategic advantage over rivals, without sufficiently discussing the importance of cooperation.

Alternatively, you could discredit the field by producing low-quality analysis or framing the problem in a non-credible or sensationalist way. So, it’s important to be cautious in your efforts and base them on detailed discussion with experts.

How to contribute to strategy research?

The aim of this career is to become an expert in an important area of AI strategy, and then advise major organisations on policy.

Policy research

This path usually involves working in academia or think tanks, aiming to come up with new AI policy proposals, or more deeply understand the strategic picture. This requires more analytical skills (though almost never top end technical skills).

Some key centres of long-term focused policy research over the coming years are likely to be:

- The Future of Humanity Institute

- Allan Dafoe on Global Politics of AI at Yale University.

- Google DeepMind, or OpenAI

- Alan Turing Institute

- Cambridge Centre for the Study of Existential Risk

- Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence

These would all be great places to work. We expect more organizations to take an interest in this topic in future.

There are many other places that work on AI policy research, including many top think tanks. However, they mainly focus on short-term issues, such as the regulation of driverless cars, employment impacts, or autonomous weapons systems – rather than the long-term issues around ensuring AI is designed safely.

Nevertheless, they can be a good place to work to build skills and connections, or try to tilt the debate towards longer-term issues. Some of the top centers for short-term focused AI policy research are:

- Campaign to Stop Killer Robots

- The Brookings Institute

- Amnesty International

- Centre for New American Security

- Partnership on AI

Learn more in our full profile on think tanks.

Policy practitioner

Practitioners implement policy rather than develop new policy. These positions are hugely influential, so it’s important they’re filled by people who understand the issues. These positions require relatively stronger social skills compared to policy research.

It’s not clear yet where the best place to end up would be to implement AI policies over the long term. This means it’s important to build your career capital and be capable of taking opportunities as they arise.

To do this, gradually aim for higher and more relevant positions in either the executive or legislative branches and be opportunistic if, for example, changing political climates favor different agencies.

Examples of options that could become valuable include:

- The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, and the National Science Foundation.

- Being a science advisor to a Member of Congress (or member of any other national parliament). In particular, it would be attractive to be an analyst in a relevant committee, such as the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, or work with any committee chair.

- Working in IARPA or DARPA, which are leaders in AI funding.

- Within defense, the National Security Council or the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

- Anywhere close to the top of federal governments (e.g. cabinets, the foreign service).

- The United Nations (e.g. UNICRI or UNODA).

- The European Commission, which is similar to a national government. For instance, the European Parliament Commission on Civil Law Rules on Robotics has made recommendations, which the European Commission is now considering.

- Senior roles within the technology companies listed below.

Within governments outside the USA or EU, there are often similar institutions.

Many of these positions also put you in a good position to contribute to other urgent problems, such as pandemic risk and nuclear security.

How to prepare yourself for strategic research

We spoke with a researcher in the field who suggested the following ways to build qualifications and advance.

First, careers in policy and strategy require opportunism and the use of connections. You will want to position yourself to take a role in government during big shifts in power.

There is a chance of advancing very quickly, so it’s worth applying for top roles as soon as possible (so long as you have a back-up plan).

Alternatively, take one of the following to build career capital for the top positions. All are useful, so choose between them based on personal fit. Also consider pursuing several at once, then go whereever you get the best opportunity.

- A technical Master’s or PhD in computer science, economics, statistics or policy (Masters of Public Policy or International Relations). These are useful for credibility, as well as understanding the issues. A PhD may be overkill in some cases, but especially helps with science grantmaking.

- Go work in an industry or company that is already developing AI, e.g. Google.

- Work in any job that gives you policy connections. In the US that could mean being a staffer for a Congressperson; working in a think tank; or a leadership position in government such as the Science and Technology Policy Fellowship, Presidential Management Fellowship, or White House Fellows. In the UK, that could mean being a researcher for an MP, joining a think tank, working in the foreign service or joining the Civil Service Fast Stream.

- It can be useful to build up expertise and credibility in government agencies that are likely to have a stake in the issues, for example in the Office of Navy Research, DARPA, IARPA, Homeland Security Advanced Research Projects, or United States Digital Service.

In most of the organizations above, research into problems caused by AI represents only a small part of what they do, creating the risk that you’ll develop expertise or connections that are not relevant.

Our advice is as follows:

- Go work directly on relevant AI strategy research at groups like the Future of Humanity Institute if you are already qualified to do so.

- Otherwise, work on short-term policy issues arising from improvements to AI in think tanks, the military or elsewhere.

- If that’s not possible, go into the role which will build your skills, network and credibility the most and wait for a chance to work more directly on this problem.

Ultimately, any of the positions listed above are prestigious and will provide you with good exit opportunities to work on this or another pressing problem if you do well in them.

3. Complementary roles

Even in a research organization, around half of the staff will be doing other tasks essential for the organization to continue functioning and have an impact. Having high-performing people in these roles is essential.

Better staff allow an organization to grow more quickly, avoid major mistakes, and have a larger impact by communicating its ideas to more people.

Our impression is that the importance of these roles is underrated because the work is less visible. Some of the people who have made the largest contributions to solving this problem have done so as communicators and project managers.

In addition, these roles are a good fit for a large number of people.

Organizations working on AI safety need a wide range of complementary skills:

- HR;

- personnel management;

- project management;

- event management;

- media and communications;

- visual and website design;

- accounting.

This path is open to many people who can perform at a high level in these skills.

To get into these roles you’ll want to get similar jobs in organizations known for requiring high-quality work and investing in training their staff. We have more about how to skill up in our article on career capital.

Example: Seán Ó Heigeartaigh helped grow the Future of Humanity Institute

Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh was the Academic Project Manager (and later, Senior Academic Manager) at the Future of Humanity Institute during 2011-15, while its Director was focused on writing a book.

He played a crucial role in ensuring the Institute ran smoothly, more than doubled its funding, co-wrote further successful grants including several AI strategy-relevant grants and communicated its research effectively to the media, policymakers and industry partners.

During his time he helped grow FHI from 5 to 16 staff, and put in place and oversaw a team of project managers and administrators, including a Director of Research and Director of Operations to whom he transferred his responsibilities upon moving on.

His experience doing this allowed him to be a key player in the founding of the Cambridge Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, and later, the Centre for the Future of Intelligence. Read more…

4. Advocacy and capacity building

People who are relatively strong on social skills might be able to have a larger impact by persuading others to work on or fund the problem. This is usually done by working at one of the research organizations already mentioned.

Beyond that, the group we know that is doing this the most to raise awareness of the issue is the effective altruism community, of which we are a part. Joining and growing that movement is a promising way to increase efforts to solve the AI control problem, among other pressing problems.

Once you are familiar with the issue, you could also spend some of your time spreading the word in any of the careers that typically provide you with a platform for advocacy, such as:

You could also rise up the ranks of an organization doing some relevant work, such as Google or the US military, and promote concern for AI safety there.

However, unless you are doing the technical, strategic or policy research described above, you will probably only be able to spend a fraction of your time on this work.

We would also caution that it is easy to do harm while engaging in advocacy about AI. If portrayed in a sensationalist manner, or by someone without necessary technical understanding, ‘advocacy’ can in fact simply be confusing and make the issue appear less credible.

Much coverage of this topic in the media misrepresents the concerns actually held by experts. To avoid contributing to this we strongly recommend informing yourself thoroughly and presenting any information in a sober, accurate manner.

Example: Niel switched from physics to research management

Niel Bowerman studied Physics at Oxford University and planned to enter climate policy. But as a result of encountering the ideas above, he changed his career path, and became the Assistant Director at the Future of Humanity Institute, working on the Institute’s operations, fundraising and research communication.

Through this work, Niel was involved in raising £3 million for the Institute, contributing to doubling its size. As a result, they have been able to hire a number of outstanding additional technical and strategic researchers. Read Niel’s story…

5. Earning to give

There is an increasing amount of funding available for research in this area, and we expect more large funders to enter the field in future. That means the problem is primarily talent constrained – especially by a need for innovative researchers.

However, there are still some funding gaps, especially among the less conventional groups that can’t get academic grants, such as the Machine Intelligence Research Institute.

As a result earning to give to support others working on the problem directly is still a reasonable option if you don’t feel the other roles described here are a good fit for you.

If you want to donate, our first suggestion is giving to the Long Term Future Fund.

The manager of the fund is an expert in catastrophic risk funding, and makes grants to the organizations that are most in need of funding at the time. It’s run by the Centre for Effective Altruism, of which we’re part.

DONATE TO THE LONG TERM FUTURE FUND

Alternatively you can choose for yourself among the top non-profit organizations in the area, such as the Machine Intelligence Research Institute in Berkeley and the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford. These were the most popular options among experts in our review in December 2016. See more organizations below.

What are the key organizations you could work for?

We keep a list of every organization that we know is working on AI safety, with links to their vacancies pages, here.

The ten most significant organizations, all of which would be good places to work, are probably the following:

- Google DeepMind is probably the largest and most advanced research group developing general machine intelligence. It includes a number of staff working on safety and ethics issues specifically. See current vacancies and subscribe to get notified of new job openings. Google Brain is another deep learning research project at Google. See current vacancies and subscribe to get notified of new job openings.

- The Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University was founded by Prof Nick Bostrom, author of Superintelligence. It has a number of academic staff conducting both technical and strategic research. See current vacancies and subscribe to get notified of new job openings.

- OpenAI was founded in 2015 with the goal of conducting research into how to make AI safe and freely sharing the information. It has received $1 billion in funding commitments from the technology community. See current vacancies and subscribe to get notified of new job openings.

- The Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI) was one of the first groups to become concerned about the risks from machine intelligence in the early 2000s, and has published a number of papers on safety issues and how to resolve them. See current vacancies and subscribe to get notified of new job openings.

- The Cambridge Centre for the Study of Existential Risk and Leverhulme Centre for the Study for the Future of Intelligence at Cambridge University house academics studying both technical and strategic questions related to AI safety. See current vacancies and subscribe to get notified of new job openings.

- The Berkeley Center for Human-Compatible Artificial Intelligence is very new, but intends to conduct primarily technical research, with a budget of several million dollars a year. See current vacancies and subscribe to get notified of new job openings.

- The Future of Life Institute at MIT does a combination of communications and grant-making to organizations in the AI safety space, in addition to work on the risks from nuclear war and pandemics. See current vacancies and subscribe to get notified of new job openings.

- Alan Dafoe’s research group at Yale University is conducting research on the ‘global politics of AI’, including its effects on international conflict. PhD or research assistant positions may be available.

- AI Impacts is a non-profit which works on forecasting progress in machine intelligence and predicting its likely impacts.

Learn more

The top two introductory sources are:

- Prof Bostrom’s TED talk outlining the problem and what can be done about it.

- The Artificial Intelligence Revolution, by Tim Urban at Wait But Why. (And also see this response).

After that:

- The key work describing the problem in detail is Superintelligence. If you’re not ready for a full book try this somewhat more technical article by Michael Cohen.

- If you want to do technical research our AI safety syllabus lists a range of sources for technical information on the problem. It’s ideal to work through these articles over a period of time.

Robert Wiblin

Rob studied both genetics and economics at the Australian National University (ANU), graduating top of his class and being named Young Alumnus of the Year in 2015.

He worked as a research economist in various Australian Government agencies, and then moved to the UK to work at the Centre for Effective Altruism, first as Research Director, then Executive Director, then Research Director for 80,000 Hours.

He was founding board Secretary for Animal Charity Evaluators and is a member of the World Economic Forum’s Global Shapers Community.

Original post https://80000hours.org/problem-profiles/positively-shaping-artificial-intelligence/