By the FBI

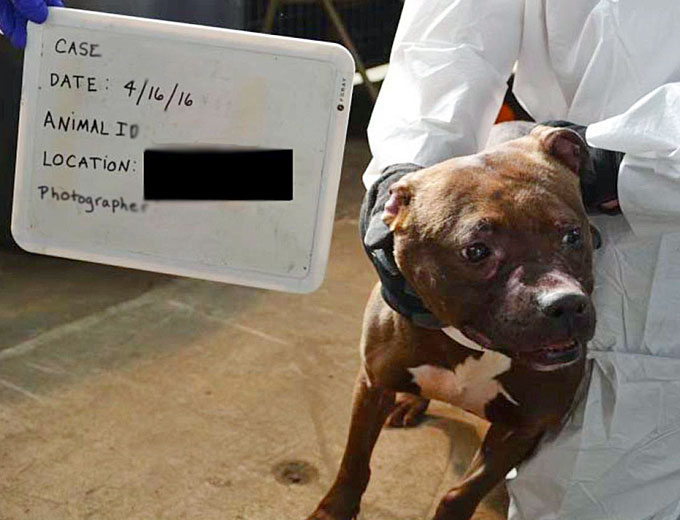

A New Mexico man’s long journey through the legal process for his extensive role in a dogfighting network — from his arrest in 2016 to his guilty plea last year to his sentencing last month — raises a logical question:

What happens to the rescued dogs as the case is wending its way through the courts?

Robert Arellano, of Albuquerque, was sentenced April 4 in federal court in New Jersey to four years in prison for his involvement in a multi-state dogfighting network.

When he and others were arrested in a coordinated operation spanning five states and the District of Columbia, investigating agencies, including the FBI, rescued 85 dogs.

What happened next was a tightly orchestrated process involving the U.S. Marshals Service, animal rescue organizations, federal agents, and a small cadre of Department of Justice (DOJ) prosecutors and federal forfeiture attorneys.

Their collective goal, refined over years, is to get recovered dogs screened, treated, rehabilitated when feasible, and, if appropriate, adopted out to new families as soon as possible.

(A foster family took in six puppies from a rescued pit bull terrier. They were all successfully adopted. One of the puppies named Porkchop, shows how civil asset forfeiture laws are being applied in dogfighting cases to speed up the recovery of rescued dogs and position them to be legally adopted. Courtesy of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and YouTube. Posted on Jun 25, 2019.)

Most dogs found in fighting operations used to be euthanized, in part because they could not be adopted until a criminal case ran its lengthy course, leaving the animals to languish.

But in recent years, the recovery and placement process has been streamlined by using a legal technique commonly associated with drug dealers, fraudsters, and terrorist financiers—civil forfeiture, in which property involved in a crime can be legally seized before an indictment or a conviction (in this case, the dogs).

“Typically, when you’re dealing with cash or jewelry or some other inanimate object, it doesn’t matter if you wait until the end of the criminal case to deal with it,” said Mary Hollingsworth, an attorney with the Wildlife and Marine Resources Section in DOJ’s Environment and Natural Resources Division (ENRD).

“Dogs may start to decline physically and psychologically after about six months, even in the best shelter setting.”

“They are not meant to be in cages with limited human interaction and exercise for long periods of time.”

Federal enforcement of dogfighting falls under the Animal Fighting Prohibition Enforcement Act of 2007, which targets individuals directly involved in animal blood sports and prohibits interstate trafficking of animals for fighting.

In 2014, federal animal protection statutes were added to ENRD’s portfolio.

The division quickly established best practices, including using civil forfeiture laws to expedite the care of seized dogs while ensuring property owners are afforded an expedient opportunity to assert their interest in the animals.

In some cases, criminal suspects simply relinquish their dogs upon arrest or shortly thereafter.

“This is all just for the better welfare of the animals. Because the more efficiently we can get through this process, the quicker these dogs can get adopted out to better homes.”

Shellie Roth, forfeiture paralegal, FBI Columbia

“If we have to go through the civil forfeiture process in dogfighting cases, it takes on average about three to four months,” said Hollingsworth.

“That’s significantly shorter than the criminal forfeiture process, which addresses forfeiture only after conviction or through plea negotiations.”

Almost 1,000 dogs have been seized through ENRD’s civil forfeiture process in the past three years, Hollingsworth said.

FBI operations involving animal seizures are well planned, with ENRD lawyers and the U.S. Marshals—who contract with animal rescue organizations—notified well in advance so they are prepared to sweep in after arrests.

The process allows for qualified vendors who specialize in animal care and management to assist with the on-site seizure of the animals; provide veterinarian care, kenneling, and adoption services; and support investigators and prosecutors on their case.

Meanwhile, ENRD works closely with federal agencies, such as the FBI, to efficiently complete the forfeiture so the adoption process can start.

That’s how Laura Donaldson ended up with six puppies to foster in 2016.

They were among 64 dogs seized from 10 homes in Illinois as part of a coordinated operation by the FBI’s Quad-Cities Federal Gang Task Force and the Rock Island Police Department.

A rescue organization took custody of all the dogs, and the six litter mates were taken in by Donaldson, a veterinary technician with a soft spot for big dogs.

She said the puppies were only three weeks old when she got them.

They were offspring of another rescued dog who had been groomed to fight and had to be euthanized.

Donaldson spent a few months socializing the puppies with her other four dogs and a neighbor’s large family.

She was able to find adoptive homes for the dogs while they were still puppies because of the civil forfeiture.

“They’re just happy little guys,” said Donaldson, who kept one of the puppies. She named him Porkchop; he’s now 3 years old and weighs 60 pounds.

“I certainly was very happy when things went through quickly.”

Three years later she still gets pictures and notes from the families of her former foster pups.

“They’ve all turned out great,” she said.

Animal welfare experts and law enforcement officials say dogfighting is more common than most people think.

A 2015 poll by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) indicated that half of law enforcement officers nationwide encountered dogfighting—a felony in all 50 states—in their line of work.

FBI investigations, meanwhile, have shown there is often a nexus with other forms of criminal activity, such as drug dealing or gambling.

“It’s very organized and very underground,” said Samantha Maxwell, a special agent in the FBI’s Springfield (Illinois) Field Office, who was the FBI gang task force coordinator during the 2016 investigation.

The U.S. Marshals and the ASPCA managed the dogs’ rescue and seizure.

In January 2016, the FBI began tracking crimes against animals the same way it tracks other felony offenses like homicide and kidnappings.

By creating a category within the Bureau’s National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), law enforcement agencies can get a better handle on the problem—and how to assign resources to it.

The most recent NIBRS report for 2017 shows more than 3,200 animal cruelty incidents were reported during its first year of data collection.

(WARNING: Graphic Images. People who hurt animals are more likely to escalate their abuse to humans, but a new way of reporting could reduce both types of abuse. Courtesy of 41 Action News and YouTube. Posted on Jan 7, 2016.)