An Ancient Mystery

In 1915, when American explorers entered an ancient tomb cut in the parched limestone cliffs of the eastern bank of the Nile River, 155 miles south of Cairo, they were greeted by the disembodied head of a 4,000-year-old mummy.

But whose head was it?

The mystery has plagued scientists for more than a hundred years, until the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) recently used advanced DNA sequencing technology to help confirm the identity.

Although looters had long since ransacked the tomb of any precious metal treasures, the tomb did contain historical and archeological treasures including a collection of funerary artifacts and two intricately painted cedar coffins.

On one of the coffins sat the lonely head, mummified according to an archaic method common during the Old Kingdom (2686-2181 B.C.) – sculpting linen bandage with padded eyes and lips, and painted facial features.

The explorers also found a headless torso and what was left of another mummy lying scattered on the floor.

Those explorers, who were from Harvard University and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, knew the mummy remains were not of a pharaoh but of the wealthy governor Djehutynakht and his wife who lived in the 15th Egyptian province around 2000 B.C. during the Middle Kingdom period (2050-1800 B.C.).

But archeologists weren’t sure whom the single head they found belonged to – the wife or the governor.

(Four thousand years ago, an Egyptian dignitary and his wife were interred in a tomb on top of a rugged cliff. When excavators from the MFA opened the tomb in 1915, tomb robbers had already ransacked it. Amid the disarray, a severed mummy’s head was found. Was it the governor (Djehutynakht) or his wife? What could it teach us about mummification practices? Scientists at Massachusetts General Hospital studied the mummy’s head to find clues. In this video, Dr. Rajiv Gupta explains what they found… and what mysteries remain. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and YouTube. Posted on Nov 3, 2009)

By funding cutting-edge scientific research together with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and providing DNA-sequencing expertise and technology S&T was able to help.

It was not for lack of trying that researchers could not identify the remains.

They made some progress in 2005 when a Computerized Tomography scan revealed that some of the facial bones, which can help determine the sex, were altered postmortem.

The Museum and a myriad of biologists had tried to test the DNA, but were unsuccessful due to its severely damaged, fragmented state.

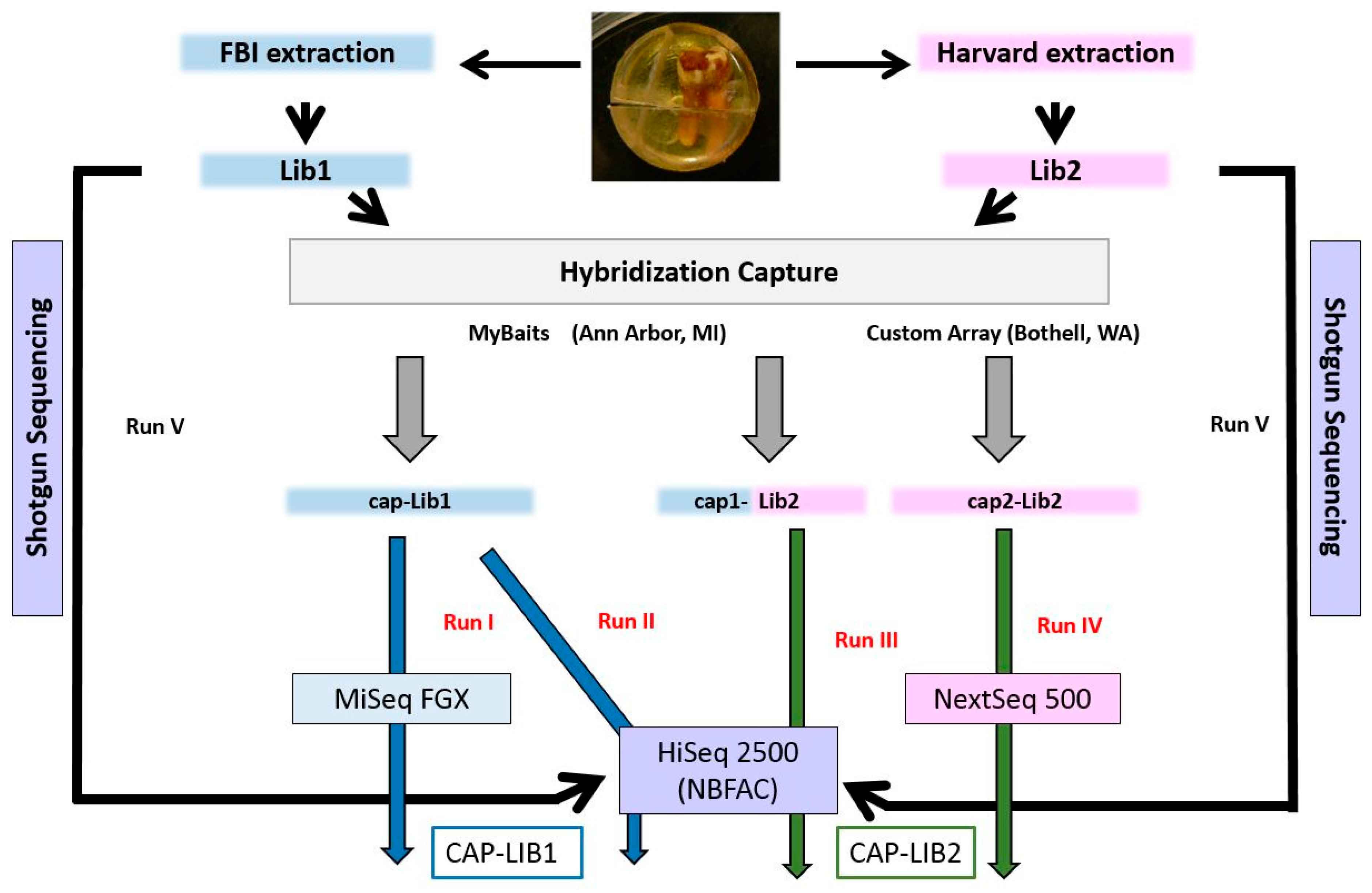

Because it could not be studied via the typical DNA sequencing methods, which require long DNA fragments, the FBI used a next generation DNA sequencing method with Harvard University and later asked S&T to help solve this ancient mystery.

Present Day Impact of a 4,000-Year-Old Mummy

The results published in a recent study are applicable not only for ancient human remains but also for forensic analysis of the most decomposed and degraded specimens.

The FBI released the paper on March 1, which S&T’s National Bioforensic Analysis Center (NBFAC) of the National Biodefence and Countermeasure Center (NBACC) contributed to.

“The methods used in this study published in a peer reviewed journal are broadly applicable to many types of federal law enforcement attribution cases trying to link a person to a crime, including those that involve weapons of mass destruction and terrorism, which is in S&T’s mission space,” said Dr. James Burans, forensics specialist from NBFAC.

“This method will very likely continue to improve, as improvements in the sequencing technology are really what are driving it forward.”

This research opens the possibility of using genomic analysis in a wider variety of FBI cases, which often involve burned bones, old hair and other types of severely compromised evidence material that is difficult to analyze with the traditional methods.

In ideal conditions, like cold, dry and dark places, human DNA can survive from about 500 years to 100,000 years. When left out in the elements like in hot and humid environments, DNA becomes unusable in as little as a few weeks.

The FBI performed the first tests on the mummy’s DNA in 2016 and then sought Harvard University to repeat the tests and confirm the results because of their premier ancient DNA laboratories.

To develop additional data, the FBI asked S&T last summer to run both FBI’s and Harvard’s samples on an NBFAC high capacity sequencing instrument called the Illumina HiSeq that generated a lot more data than the FBI’s instruments and could effectively probe deeper into a sample than before.

“Additional sequencing for both FBI’s and Harvard’s samples was done at NBFAC,” said Dr. Nicholas Bergman, the head of the genomics department at NBFAC.

Researchers used the mummy’s tooth as a specimen because it could still contain viable genetic material since teeth are some of the most durable parts of the human body.

NBFAC also did the subsequent computational analyses for this study and helped write the paper.

“This was the first time that anyone was able to successfully extract and analyze nuclear DNA from this type of sample,” said Dr. Bergman.

The successful testing of the mummy’s tooth is relevant for the FBI and other federal agencies such as the DHS Components, U.S. Customs and Border Protection and the U.S. Secret Service.

“Even though this DNA sequencing is new, being published in a peer review journal supports the admissibility of the data that we generate for federal prosecution,” said Dr. Burans.

This applicability piqued the interest of an FBI researcher Dr. Jodi Irwin back in 2011 when the Museum asked her to test the DNA from the mummy’s tooth while she worked for the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory, but she couldn’t test the mummy’s DNA because the lab did not accept the tooth.

(Learn More. A museum wasn’t sure whose head they had put on display. That’s when the F.B.I.’s forensic scientists were called in to crack the agency’s oldest case. Courtesy of MagZone and YouTube. Posted on Apr 2, 2018)