By Kevin Fogarty, Semiconductor Engineering

Despite the high risk of a market filled with billions of at least partially unprotected devices, it is likely to take five years or more to reach a “meaningful” level of security in the Industrial IoT.

The market, which potentially includes every connected device with an integrated circuit, is fragmented into vertical industries, specialty chips, and filled with competing OEMs, carriers, integrators, networking providers.

There are so many pieces, in fact, that it is difficult to dovetail all of them into a workable number of best practices and standards specifications, according to Richard Soley, executive director of the Industrial Internet Consortium and chairman and CEO of the Object Management Group.

(Learn More. IIC Executive Director Richard Soley is interviewed at the IoTSWC in Barcelona, Spain. Dr. Soley talks about everything from the IIC’s beginnings to the importance of testbeds. Courtesy of IIConsortium and YouTube. Posted on Jan 11, 2017)

One of the biggest hurdles is unifying all the various factions involved in the Industrial IoT behind a relatively small, well-defined set of definitions of what security actually is and how to get chipmakers to build it into their products consistently.

“A lot of it’s already pretty standard, so that shouldn’t be too bad” according to Mike Demler, senior analyst at The Linley Group.

“There’s no standard architecture for the security of an IoT chip, so there are different approaches to that.”

“But the concept of a secure boot is pretty well defined and so is the concept of a secure element.”

“It’s just up to the designer how to implement them.”

The market for microcontrollers is very fragmented, which is part of the reason Arm introduced its Platform Security Architecture (PSA) program last October.

The company provides open-source software and higher-level APIs to make it easier for developers to write trusted code, according to Neil Parris, director of products for Arm’s IoT Device IP business unit.

“We’re writing documentation with suggested recipes of what needs to go into a PSA chip for various security levels,” Parris said.

“We provide a library of trusted functions and APIs because most developers don’t particularly want to write trusted code.”

Many chipsets are also based on, or include, Arm’s Cortex M series chips, which provide basic security functions tailored to their power level.

But chipmakers don’t necessarily implement all the functions available in the Arm IP in a particular chipset, or use what they do implement in a consistent way.

“The hardware is different for every vendor,” said Asaf Ashkenazi, vice president of IoT security products at Rambus.

“Even if you only look at the root of trust, each has a different way of doing that, different memory restrictions in the device, for example,” according to Ashkenazi, who led a team cataloging such changes in IIoT chipsets in order to build the SDKs customers can install to give the cloud-based Cryptoquote service the ability to access, monitor and send commands to devices running the most common IIoT chipsets.

Intel’s Enhanced Privacy ID and Arm’s PSA are ways to build basic security into silicon before the chips or IP are incorporated into larger chipsets.

Microsoft’s Azure Sphere announcement in February addressed similar issues, but on such a narrow, platform-dependent basis. That doesn’t apply to most of the IIoT in the same way an effort like PSA might, said Demler.

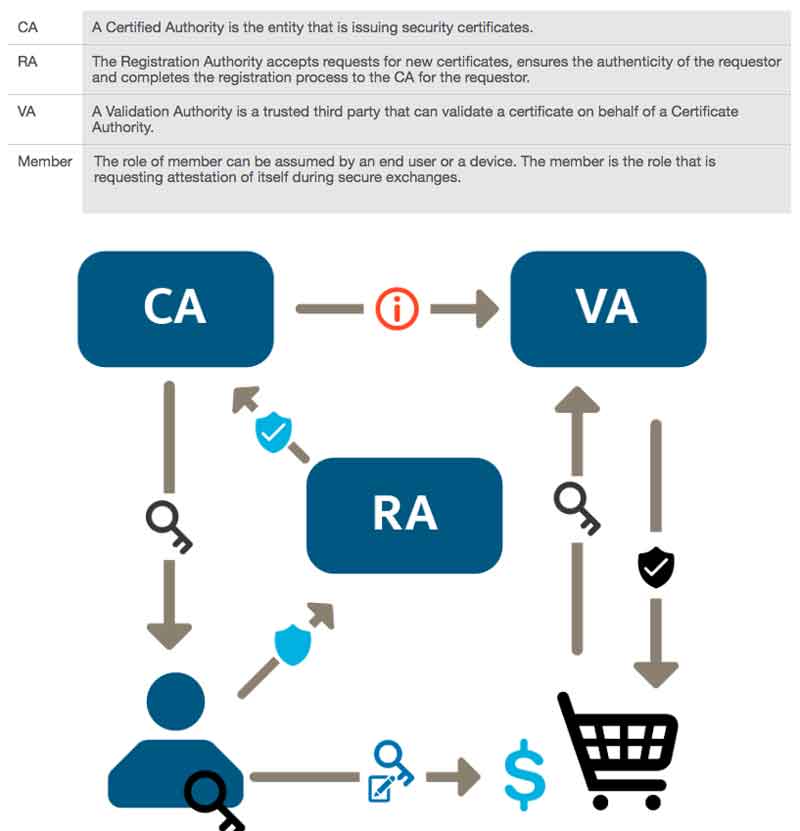

Fig. 1: Intel’s public key infrastructure and flow. Source: Intel

“The cheapest thing would be to integrate security inside the chip – design in a root of trust, key material, crypto accelerator and key essential security services, spending on what package it’s a part of, and you have something to provide a root of trust that takes up a tiny fraction of a square millimeter,” Parris said.

“That gives you the attestation method and authentication anchored in hardware so the day the chip is born you have the method to prove its properties and authentication to know that it’s something you want, not a hacker.”

Bigger problems

There are more hurdles to cross than simply getting chipmakers to make IoT devices boot securely, however.

The most obvious problem from a customer perspective is the inability of most organizations to see or identify an average of 40% of the devices on their networks, or know what they’re doing from moment to moment, according to Lumeta, a security monitoring firm whose analysis of the IoT infrastructure of 200 organizations was an important part of Cisco’s 2018 Annual CyberSecurity Report, released in February.

The divide in perception, experience and divergence in decision-making between OT and IT technical staffs at customer companies seems to be at least as significant as any technical issue, however.

Members of the operational technology staffs responsible for the factory automation and sensor projects, and smart factory or automated supply chain projects, tend to think of security as being built in to their systems.

They have to be reminded that projects don’t sit isolated and safe behind a firewall at the factory, Soley said.

Once a device is connected to the Internet, however, the idea that a device can remain protected goes out the window and the technical staff becomes responsible for investigating potential security risks in each piece of software and at each layer of the communications stack, said Gerardo Pardo, CTO at Real-Time Innovations.

One out of three industrial sites has a direct Internet connection, according to an October, 2017 report from ICS security provider CyberX, which analyzed network traffic from 275 industrial customers from the US., Europe and APAC.

CyberX also found that:

• 60% of industrial organizations allow passwords to cross OT networks unencrypted;

• 50% run no antivirus software;

• 82% use remote-management protocols that are vulnerable to digital reconnaissance;

• And three out of four reported using at least one controller running a version of Windows for which Microsoft no longer provides patches.

Success rates are about what you’d expect from that kind of beginning, too.

Cisco reported last year that respondents considered only 26% of the projects they cited as successes.

Of the rest, 60% stalled at the proof-of-concept stage and a third were failures, mostly for reasons that boiled down to unfamiliarity with the technology, the process and the internal and external partnerships required.

Only 8.5% of industrial organizations responding to a survey said they were “very ready” to address cybersecurity, but more than a quarter said they’d had a cyber attack or other security incident within the past 12 months, according to professional-services and business-consulting firm Sikich LLP.

Sikich also found that 77% of its customers have no plans to implement IIoT technology yet.

IT or InfoSec specialists are at least a little more likely to make sure IoT devices don’t have weak default passwords and check to see if they’re encrypted before being sent over a network, though there’s no guarantee of that, according to Steve Hanna, senior principal at Infineon Technologies.

On the other hand, information security people who focus on hack prevention tend to forget that “security” includes the need to be sure smart factory or transportation equipment doesn’t kill anyone or break down every day.

“In a typical IT environment you can shut things down or block ports to respond to something you don’t like,” Hanna said.

“In an OT environment, if you block a port you may not be able to see the pressure level inside a vessel. You often can’t do a port scan of OT systems.”

“Many of them will crash if you scan them for vulnerabilities. And in OT, having a backup to take over if the primary fails doesn’t make sense.”

“Attackers are now going after the safety systems, as well as destabilizing the main system.”

“So you start out thinking you have suspenders and a belt, and they’ve cut them both so you’re not protected at all.”

There are a lot of other things that tend to be overlooked by both OT and IT lifecycle issues.

This includes when and how to de-commission old sensors, or identify devices that may have been compromised. Removing them is an important part of the whole picture, as are over-the-air updates that allow patches to be installed, said Vic Kulkarni, vice president and chief strategist for the Semiconductor Business Unit at ANSYS.

“Security has become a regular point of discussion with customers at conferences,” Kulkarni said.

“You have to manage the heat signature, antennas, how you decommission nodes if they become hostile, and if your techniques are too cumbersome it can be expensive and you get pushback.”

“This is an ecosystem. One supplier can not do it all alone. So we need to figure out how to incorporate security software, and privacy for health care, without messing up the balance of PPA. It’s a real ‘whack-a-mole’ situation.”

(Interviews of Vic Kulkarni, ANSYS Prof. Ikhlaq Sidhu, Center for Entrepreneurship & Technology, UC Berkeley, Dr. Tim Saxe, Chief Technology Officer, QuickLogic. Courtesy of Vic Kulkarni and YouTube. Posted on Jun 9, 2016)

Discussions with customers, and coordination with OT, IT and other players, is key to pulling the IIoT world together enough to build some level of coherence, according to Ranjeet Khanna, director of product management, IoT and embedded systems for Entrust Datacard.

“One gap has been that most of the discussions on IoT security are happening in operational environments, with device operators, IoT consumers who are taking technologies and trying to build use cases and applications on top of them,” Khanna said.

“If those discussions are just one on one, what about the rest of the OEMs and device makers? How will I know how to issue a certificate to a device?”

“These are the gaps in how we should educate our peers. We have a unique opportunity with the IIoT, but also a responsibility to create a foundation for IoT security.”

“We live in a world of competition, but we can compete with standards that also let us provide a complete product.”

“My goal is to sell my product or services, but not by offloading tons of responsibilities onto customers and elude my own responsibility.”

Original post https://semiengineering.com/why-iiot-security-is-so-difficult/